Simbalien

Simple but alien

Delve into science and phenomena with a fresh, simplified approach to understanding the universe.

Curiosity Unleashed

★★★★★

No, the focus of this website is not first grade education of extraterrestrials. The purpose of the site is to explore how ideas that make our senses uncomfortable might be applied (relatively) simply to solve problems.

Some examples may be of help to explain this. Take the image below:

A boy looking to the right through binoculars. But the Microsoft Paint Copilot AI that generated it had to be told to produce a boy looking to the left through binoculars. It appears that the perspective of the AI is “inside the computer looking out”. You have to imagine the image you want from this perspective, which isn’t so very alien but is a little weird. But the fix is really simple.

Another example has been around for 120 years. We see references to it frequently enough in the media that we may feel that it has been normalized. The subject is special relativity.

Say you are traveling in a spacecraft at escape velocity, about 8 kilometers/second. A light ray passes by at the familiar speed of 300,000 kilometers/second. It naturally feels right that the speed of the light ray relative to you should be 299,992 kilometers/second. It is not. Its speed relative to you is 300,000 kilometers/second. The speed of light must be the same for all observers. To most everybody living in 1905 when Einstein first published his paper on special relativity, this would have seemed alien.

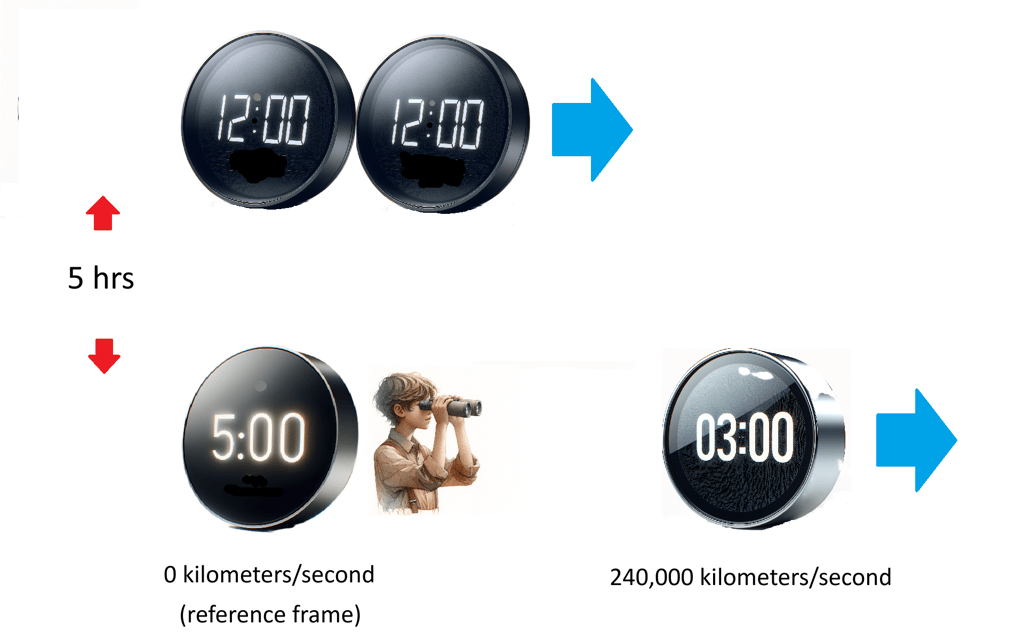

A result of this is time dilation.

Suppose one clock showing 12 o’clock and moving at 240,000 kilometers/second relative to the boy as observer passes another clock, also showing 12:00, which is stationary relative to the boy. When the boy’s local clock shows 5:00, the other clock will show 3:00. (Since this other clock is moving away from him at 4/5 the speed of light, he will not actually see the 3:00 image with his amazingly powerful binoculars until 4 hours later, but he can still deduce that the clock showed 3:00 relative to him when his local clock said 5:00.)

The ideal of time dilation, that a clock moving away from us appears to move slower than one not moving relative to us, should seem alien, just as light having the same speed relative to all observers is. Yet once the result about light speed is accepted, the amount of time dilation as a function of speed is easily determined using a simple application of the Pythagorean Theorem (See any source on special relativity). Simple but alien.

Finally, take the idea of “nothing”. We think we can conceive of it, say as below.

Of course, black is only the absence of visible light, not necessarily of everything. The entire universe before ionization could be hidden in there.

The problem with “nothing” is really the problem with “everything”. (We are talking about an unqualified “everything”, not some reference like “everything in the room”). “Nothing” is a condition such that if you have something, that something is not in “nothing”. Where does something come from? Everything. So “nothing” must not contain anything that is in everything.

OK, the above paragraph seems exceptionally silly. We have to get a little technical to realize why it points to a problem. Suppose we have two sets A and B. We say A has more elements than B if after matching each element in A to exactly one element of B, and no element of A or B is involved in more than one match, some element of A is left unmatched. Take {1, 2} and {3}. Match 1 to 3 and 2 is left over. Trivial, for finite sets. Now take the set of counting numbers {1,2,3,…} and the set of real numbers. By the same reasoning, it can be shown that there are more real numbers than counting, even though both sets are infinite.

Even for infinite sets it can be shown that the set of subsets of a set has more elements than the set itself. What is everything if not the set of all somethings? So the set of all sets of somethings has more elements than everything. But that is absurd, since a set of somethings is itself something, and belongs to everything. So everything has more somethings than everything. In other words, our notion of nothing as the absence of everything does not work, as “everything” is ill-defined.

Problems similar to that with “everything” above were recognized around the turn of the 20th century. Mathematicians use well axiomatized rules for handling sets, all of which must be subsets of a “universal set”, to avoid the problems one can have with “everything”. The null set would then correspond to “nothing”.

Nature or our reality is difficult to axiomatize, however, as the difficulty reconciling general relativity and quantum mechanics demonstrates. There could be an advantage in ”nothing” being inconsistent. The great question of how the universe could have come from nothing might be answered that something was always there. To forbid any something from being there is to forbid everything, an inconsistent concept.

All the above discussion saying that even the concept of “everything” is inconsistent must seem alien to most readers. We don’t like the idea that when we conceive of something as familiar as everything (without qualification) we are being inconsistent. But the inconsistency of “everything” does lead simply to the inconsistency of “nothing”.

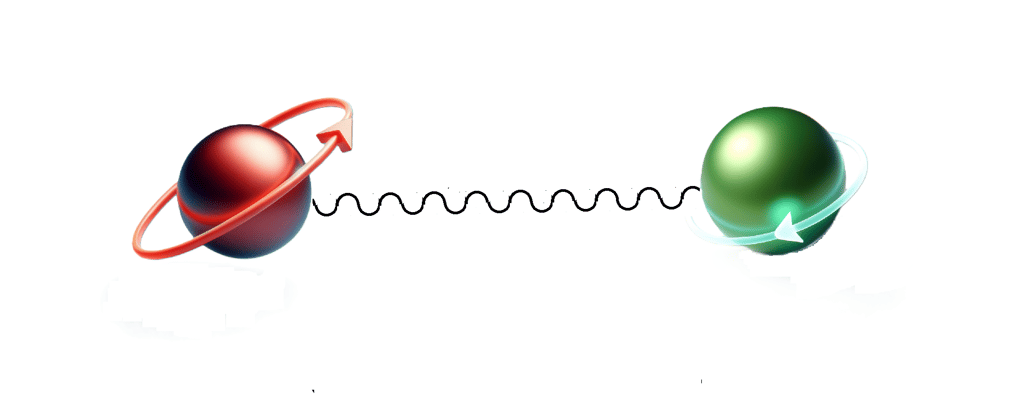

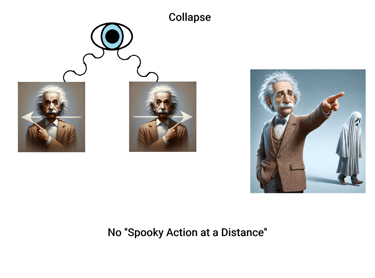

OK, where can we go with the idea of “simple but alien”? One thing we can look at is what is popularly called “spooky action at a distance”. Quantum mechanics suggests, despite Einstein’s objections, that some information must be passed faster than the speed of light between certain “correlated” particles if they are measured in certain ways. Spin ½ particles correlated so that the total spin of the system is 0 is a common presentation of the “spooky action at a distance”.

The particles might be an electron and a positron or two electrons.

We will look at why there may not be “spooky action at a distance” in such systems. Two treatments follow: a compact one, somewhat in the manner of a technical article abstract, and an expansive one for those with some math and physics background.

No "Spooky Action": Compact Treatment

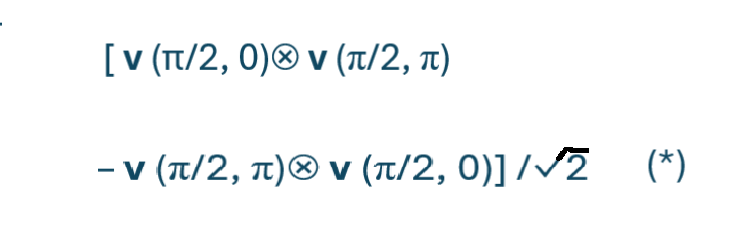

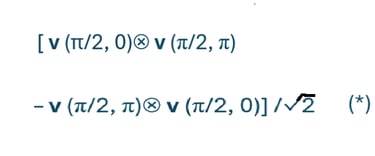

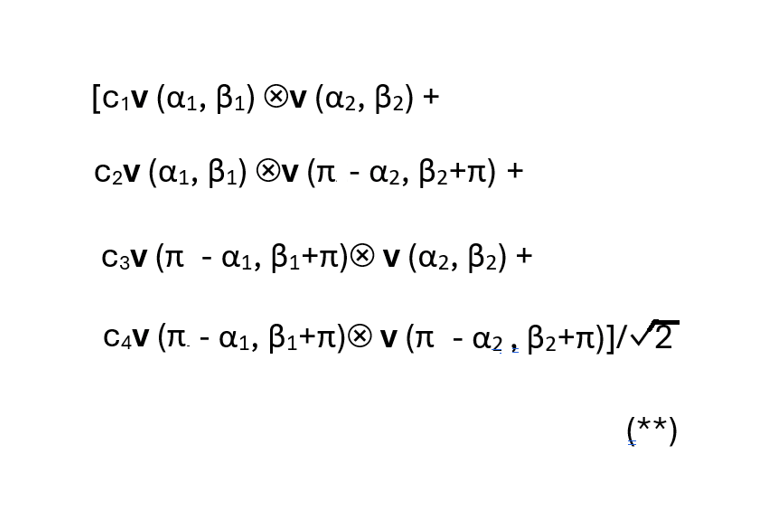

The EPR problem with local models is typically presented in the context of the correlated state

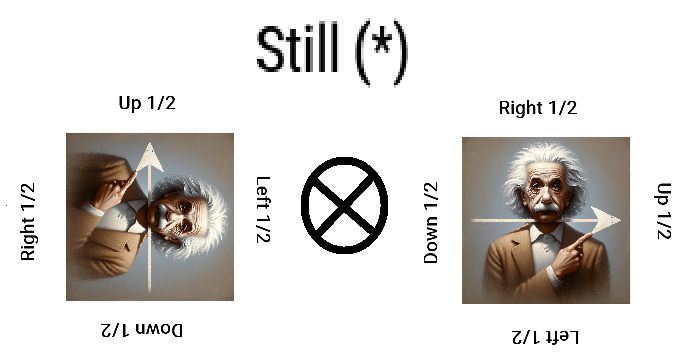

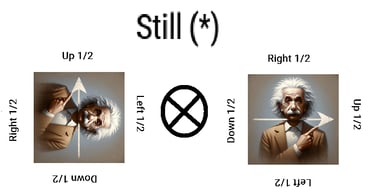

( ⟨↑|⟨↓| - ⟨↓|⟨↑| ) / √2 (*)

for two spin ½ particles. It is not possible to collapse (*) in a manner consistent with quantum mechanics using a local model, as has repeatedly been shown mathematically.

The non-relativistic view of the collapse of (*) is that first the spin of particle one is measured, and before measurement particle two takes on a state orthogonal to the collapsed state of particle one. This occurs even if the relationship of the two measurements is spacelike. Hence “spooky action at a distance”.

This view requires one of the particles to be privileged as first, which does not work if we take the relativistic view that neither of two events that have a spacelike relationship can be seen as first by all observers. This difficulty is moot if the non-relativistic (*) does not fit the real world. However, there is an experiment by Hensen et. al. (2015) (arXiv:1508.05949v1) involving two electrons within diamond chips such that the chips and measurement devices are all at rest with respect to one another. The two electrons, more than a kilometer apart, are brought into a correlated state which arguably (*) sufficiently characterizes.

So is “spooky action at a distance” necessary to collapse (*)? Note that any specification of what the direction ↑ is gives the same state (*). The direction ↑ does not have to agree with the experimenter’s bias about what “up” is. The state (*) can even be expressed as a linear combination of four tensor products, each of which represents a possible system state which could result from measuring the spin of each of the two particles in separate, arbitrary directions. This means that, for (*) to still obtain, there does not have to be agreement on what “up” or any nominal direction is between the two sites at which the particle spins are to be measured.

Now locally, the individual particle spin state ⟨↑| has no meaning without a specified direction. If an experimenter measures spin ½ in a direction he or she calls ↑, that experimenter considers the particle spin to be in state ⟨↑| . If another observer of the same experiment considers ↑ to be in a direction opposite what the experimenter thinks, then that observer will consider the particle spin state to be ⟨↓|. If neither observer’s viewpoint is considered privileged and each view is given equal weight, the particle spin is effectively in a mixture state of equal probability of being ⟨↑| or ⟨↓|. But if the particle is one of the two in the joint state (*), it was individually in that same mixture state before its spin was measured. Effectively, nothing has changed locally at the instant of measurement. Since no agreement on the meaning of a nominal direction between the two sites of measurement is required to maintain (*), both particles can remain in the same mixture of spin states at their local instants of measurement as they were in prior to measurement.

More generally, we claim that (*) remains the joint state of the two particles until the results of the two experiments are brought together, through normal light speed transmission of information, at some space-time point. Each of the two spin states forming one of the four tensor product bases of (*) represents a particle with spin ½ in some direction. As already mentioned, any choice of direction and its opposite for each particle will still produce (*) as a linear combination of the four tensor products of the associated spin states. At the space time points where the spin of each particle has been measured, we have argued that we have produced a measurement of spin ½ in an arbitrary direction which cannot be pinned down in isolation. Without a definite direction the measured spin of each particle could correspond to a spin state in any of the four tensor products which are a basis for (*). All that has been accomplished is to bring make “spin ½ in some direction” macroscopic. Before information about the results of the two measurements is brought together, (*) still obtains, even if brought into the macroscopic world.

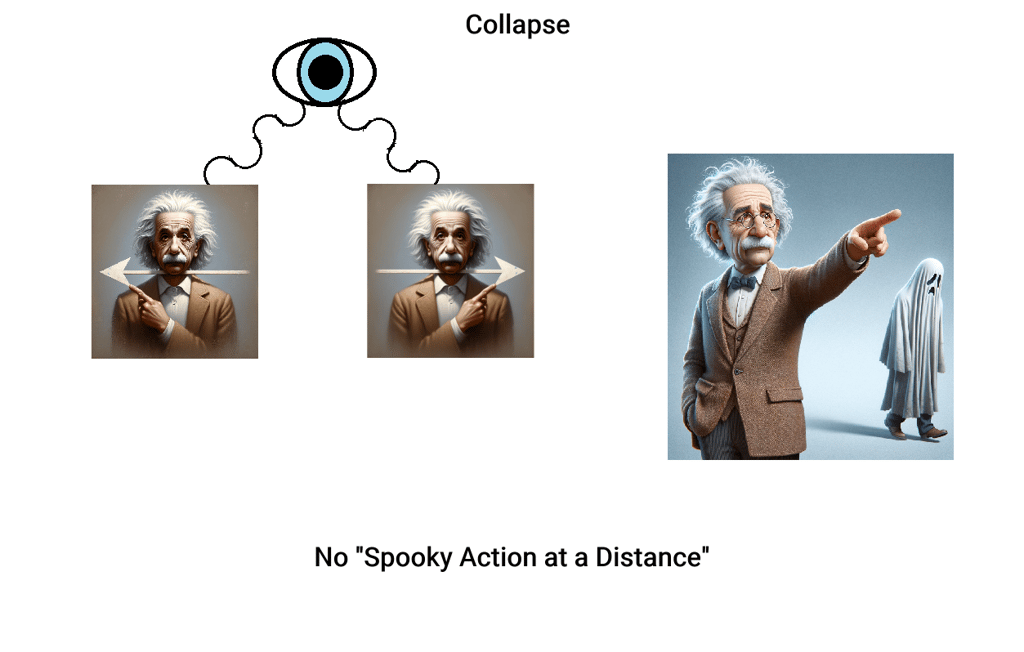

The agreement on what a direction means between experimenters measuring spins of the two particles does allow for the angle between measurement directions to be determined once the results are brought together. The combined results will correspond to only one of the possible four tensor products of spin states forming a basis of (*). Bringing information about the measurement results together produces collapse.

So (*) persists through individual particle spin measurements until information about the results are brought together at light speed, producing collapse. No “spooky action at a distance.” There is no unique space-time point for collapse, but wherever-whenever the results are combined, the results are the same because experimenters agree on what a direction means.

The argument that (*) does not require a specific determination of what a direction means or agreement on this between the sites at which the spins of the two particles are measured seems intuitively simple, though the notion that the experimenters natural sense of direction is not privileged in this experimental setup may seem alien.

The state (*) has considerable symmetry to work with. Other experimental setups looking at EPR may still involve joint states of the particles with sufficient symmetry to allow for an argument along the lines above that there is no need for “spooky action at a distance”.

No "Spooky Action": Expansive Treatment

Suppose in an experiment the spins of two correlated spin ½ particles in two random directions are measured at two points in time and space which cannot be connected by a light ray. (The space-time points have a spacelike relationship). “Spooky action at a distance” appears to be a result of an inability to represent the joint probability of measuring particular spins of the particles in a way that is consistent with special relativity. Quantum mechanics does appear to produce this probability, but it does so by assuming one particle is measured first and the result is transmitted to the other measurement at greater than light speed. This is the basic idea of “spooky action at a distance”. Since basic quantum mechanics is non-relativistic, this isn’t really a problem, but relativity makes the the space-time points at which the two measurements occur have a spacelike relationship. Neither always occurs first, as which point is “first” and which is “second” depends on the observer. This suggests both measurements must be based in part on information which was generated at some space-time point in the past of both space-time points in which the spins of the two particles are measured. This transmitted, called local, information would be sufficient to determine the two resulting spins without the direction in which one spin was measured having to be known when the other spin is measured. (These directions are random and are assumed unknowable in the common past of the two measurements.) Yet a whole body of papers, starting with J.S. Bell in 1964 (On the Einstein, Poldolsky, Rosen paradox. Physics Physique Fizika 1, 195 ), has shown this local information model cannot be achieved.

The above paragraph may leave a lot to unpack for some. And to appreciate a resolution of a problem one needs to grasp the problem. In this case grasping the problem requires some mathematical and physics experience, but at the risk of being too elementary for some, we will try to keep the explanation simple as possible. We can start with a familiar object:

The earth spins about an axis from North to South pole. It keeps spinning because about this axis because the planet has angular momentum, which is conserved, just like the familiar linear momentum, when no external force is applied. It has units of kilogram ∙ meters squared /sec. If we measure the angular momentum of the earth along a line passing through the center that is not the spin axis, a different angular momentum will be obtained. Also, the angular momentum can be thought of as a vector pointing in a particular direction, with a magnitude equal to the vector length. The angular momentum of the earth along its axis, if the axis is considered to point south, is -1 times the angular momentum if the axis is considered to point north.

Elementary particles such the electron have a special angular momentum called intrinsic spin. For the spin ½ particles the spin angular momentum can only be ½ h or –½ h, where h is the reduced Planck constant. This limitation on spin values has no analog in classical physics, since a classical body with angular momentum x in one particular direction will typically not have an angular momentum x or -x in another direction not parallel to that particular direction. This property of spin ½ particles was determined experimentally a century ago, and quantum mechanics accommodates it. (We will drop the “h” in the following discussion, treating it as if it had value 1, which is often done when its value does not affect an exposition.)

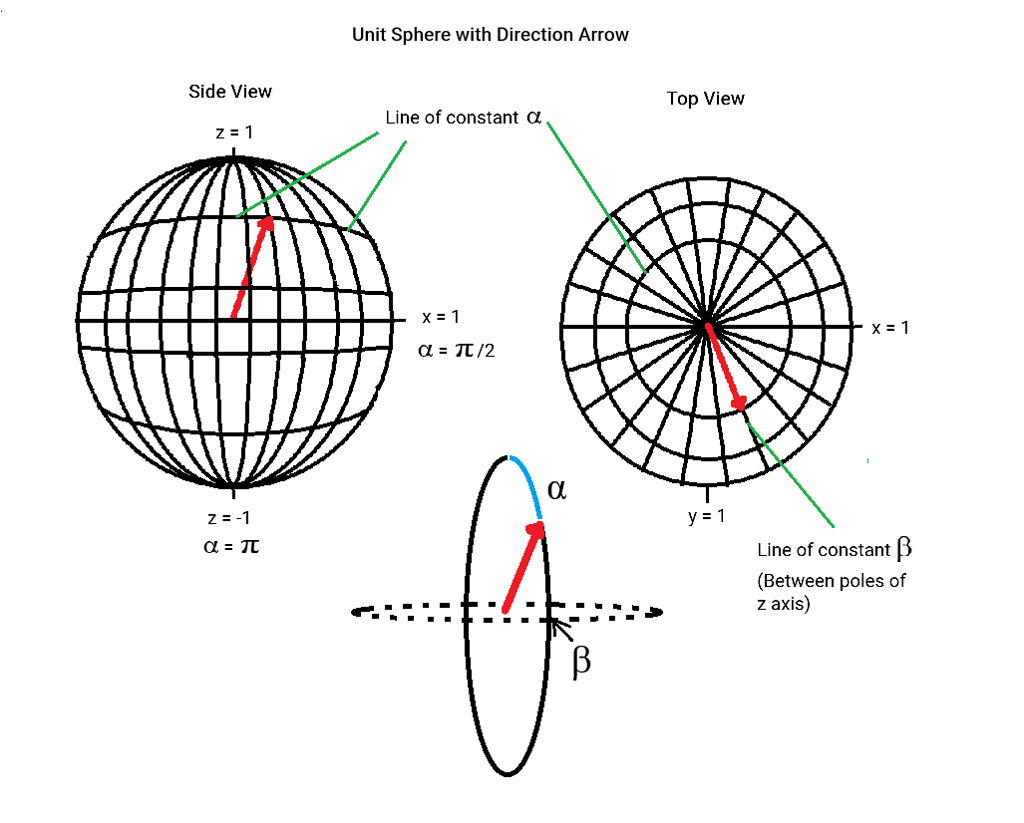

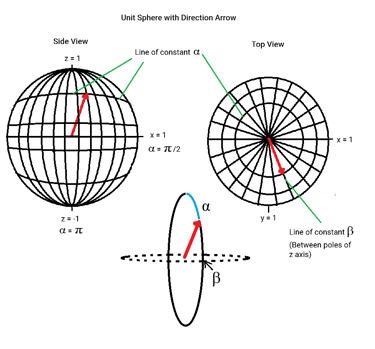

Let’s look at a mathematical model for spin ½. We use an analog to the globe above, specifically a sphere of radius 1 (because we are using the sphere to designate directions, the issue of 1 in what distance units is unimportant.) An essentially dimensionless particle, say an electron, is at its center. We are concerned with the spin of the particle in an arbitrary direction, which is specified by the co-ordinates (x, y, z) with

We can also locate a direction by specifying its “latitude” and “longitude” as on the sphere, much like a point is specified on the globe. It is convenient to think of the “latitude” angle α as ranging from 0 to π radians, and “longitude” β ranging from -π to π. These angles are typically related to x, y, and z in a convenient manner, such as α = 0 with β arbitrary corresponds to (0, 0, 1), while α = π/2, β = 0 corresponds to (0, 1, 0).

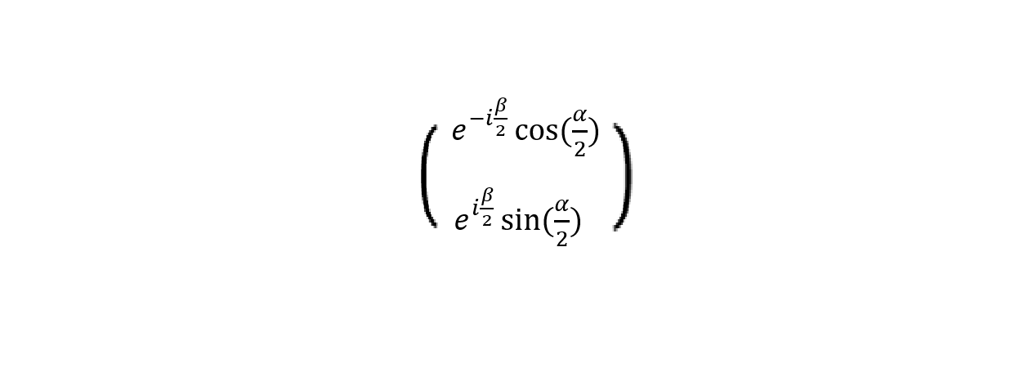

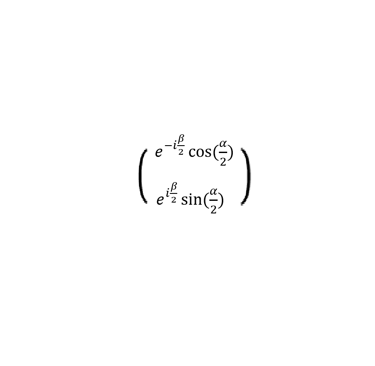

Now for the quantum mechanical treatment of spin ½. If a particle has a spin of +½ in the direction specified by α and β, we say the particle is in the spin state given by the vector

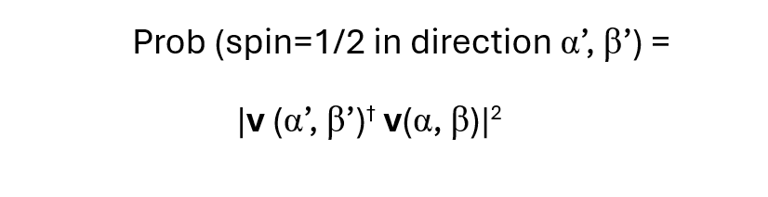

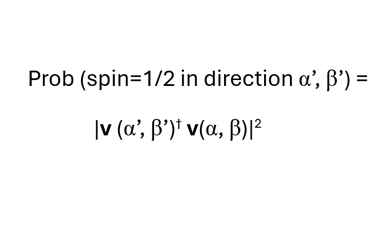

Exhaustive explanations of why this spin state is applicable can be found in many physics texts. One thing that is clever about it is that it allows for a measurement of spin in another direction to be only ½ or –½. Suppose we now measure the spin of the particle another direction α’ and β’. Let v(α, β) represent the spin state vector above, and v( α’, β’) represent the vector with α’ and β’ replacing α and β respectively in the vector above. Then the probability that the particle has spin ½ in the new direction is given by the squared magnitude of the conjugate transpose of the state vector for the new direction times the initial state vector:

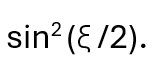

If ξ is the great circle angle between the points (α, β) and (α’, β’) then this probability will be

The probability that the new spin will be - ½ is 1 minus the probability above or

That is it. No other possibilities. We emphasize that if a spin measurement of ½ is obtained in the direction α’, β’, the spin state of the particle is now v(α’, β’) and no longer v(α, β). Measurement has changed the state of the particle. We say the measurement of the spin has collapsed the initial state v(α, β) to v(α’, β’).

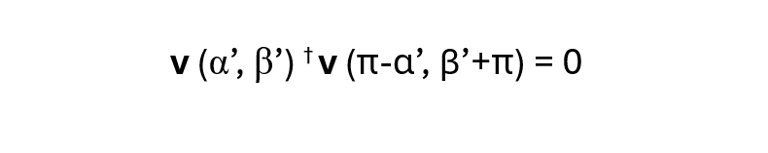

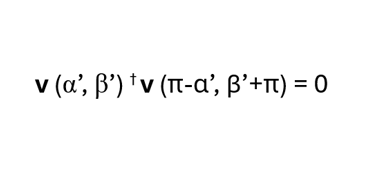

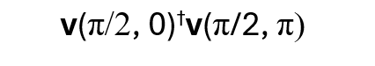

Carrying the quantum mechanics a bit further, it is important for the arguments below to note that the state vector v(α’,β’) and the state vector v(π-α’, β’+π) associated with the measurement –½ are called pure states (The arguments π-α’ and β’+π of the state vector we present for a –½ result may be out of the stated ranges, but when substituted in the formula for v given above will give the correct state). The pure states are orthogonal:

The original spin state before measurement is a linear combination, with complex coefficients, of the two pure state vectors that correspond to the two possible outcomes of the measurement.

Now on to particles with correlated states. Suppose we start with a particle with no spin at all, spin 0. Let it decay into two equal-mass, oppositely charged spin ½ particles, flying off in opposite directions. Angular momentum must be conserved, so it makes sense that if we measure the spin of both particles in one of the two directions parallel to their linear momentum vectors, the spins should have opposite values, so as to sum to 0. It further makes intuitive sense that the spins of the two particles in any direction should be opposite.

Let’s look at the quantum mechanical formulation for conservation of angular momentum with one particle flying off to the “left” and the other to the “right”. For convenience we can designate “left” as the direction (α, β) = (π/2, 0), and “right” as (π/2, π). Then the joint spin state of the particles is

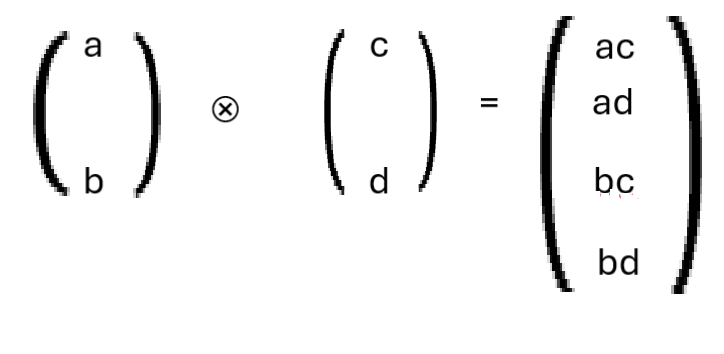

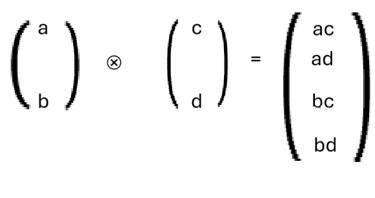

The symbol “⮾” is the symbol for tensor product. Each element of the first vector in the product is replaced by the second vector multiplied by that element, producing a 4 x 1 vector in the case of two spin states. That is,

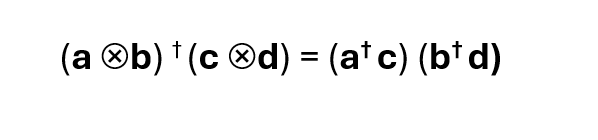

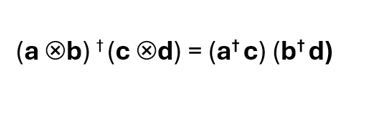

From this rule, one can work out, for vectors a, b, c, and d that

So if one particle is initially in state c and a second particle in state d, we can try asking for the joint probability of the first particle being in state a and the second being in state b after measurement by squaring the magnitude of the left hand side above. But if we square the magnitude of the right hand side of the equation we see that this is just the product of the probabilities of finding the first particle in state a after measurement and the second in b.

The state (*) is a superposition, a linear combination, of tensor products. Each pure state (1) “Left” ½ , “Right” –½, and (2) “Left” –½, “Right” ½ satisfies conservation of linear momentum along the direction of flight of the particles. But, quantum mechanically, so does (1) – (2), that is, (*). The divisor is a normalization constant, and the “-“ allows (*) to be re-expressed as we discuss below.

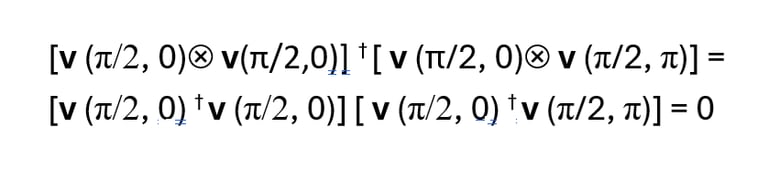

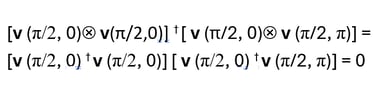

Through linear combinations of tensor products of pure states of individual particles we can create correlations between the particles. In fact, for the state (*) the values of “Left” and “Right” are perfectly anticorrelated, as conservation of angular momentum requires. The state “Left” ½, “Right” ½ is given by v(π/2, 0) ⮾ v(π/2,0). When the complex conjugate transpose of this is multiplied by the first tensor product term in (*), the result will be

because the product

is one of different, orthogonal pure states. The similar product of “Left” ½, “Right” ½ with the second tensor product term in (*) will also be 0, as will the product of “Left” - ½ , “Right” – ½ with (*). So “Left” and “Right” cannot be measured to have the same spin if the particles are initially in state (*).

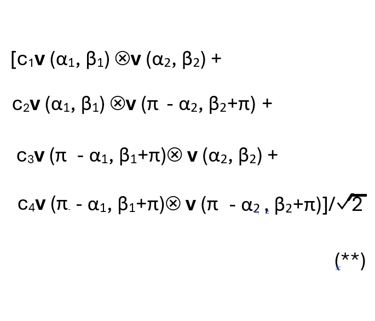

The state (*) can be expressed in terms of the directions in which we are going to measure the spins of the two particles. Using the fact that the distributive law applies to addition and the tensor operator “⮾” as it does to addition and multiplication, and that an initial spin state can be expressed as a complex linear combination of the two outcome states, some algebra will allow us to express (*) in terms of two directions

State (*) can be expressed as

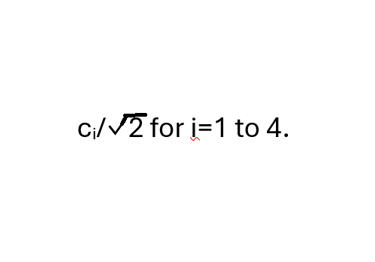

Each of the four tensor products in (**) represents one of the possible joint pure states resulting from measurements on the two particles in the prescribed directions. The dot product of the conjugate transpose of one of these states with itself just leaves 1, while its product with the other possible states in (**) will just be 0 as different pure states must be orthogonal. Thus the product of tensor product state i with (**) will yield only

(Each of the numerators of these four coefficients is a complex number which can be obtained with some algebra and trig.) Let ξ be the great circle angle on the unit sphere between

By the rule of squared modulus of dot product of complex conjugate of pure outcome state with initial state, the probability of any possible joint outcome state associated with the coefficient i will be

This probability will be either

Several caveats are now in order. First of all, the state (*) applies in non-relativistic quantum mechanics. Yet the whole point of the discussion is a supposed need for “spooky action at a distance” because special relativity limits communication between measurement of the spin of one particle and a measurement on the other. Relativistic spin ½ states are four instead of two dimensional and incorporate information on linear momentum relative to an observer. Secondly, a treatment of spin correlations between particles flying apart after being produced by the decay of a spin 0 particle should require quantum field theory, which still fortunately can sometimes reduce to something resembling (*). We would like to avoid this complexity. Thanks to one experiment that creates (*) as the joint spin state of two electrons that are at rest with respect to one another (neglecting the fact that electrons will at least have a tiny local motion), we should be able to work with (*), at least for this experimental setup.

The experiment of Hensen et. al. (2015) (arXiv:1508.05949v1) has two diamonds approximately 1.3 km apart, within each of which the spin of a particular electron is correlated with a photon that is sent to a central station between the two diamonds. Depending on how the photons arrive at the central station, it may be that the two electrons can be determined to be in the joint state (*). (We have motivated (*) with the example of two particles produced by the decay of a spin 0 particle, but this is not required to produce the joint spin state (*), as Hensen et. al. shows.) A random number generator rapidly determines in what spin direction each electron will be measured, so there is not enough time for information on what direction the spin of one electron is measured in to reach the other measurement site. The purpose of this experiment was to provide yet another better demonstration of the incompatibility of quantum mechanics with “local models”, not to dispel “spooky action at a distance”. Yet as already noted, we can use it that way.

Since the electrons in joint state (*) and the associated apparatus for measuring their spins are all a rest with each other, there is no momentum of one electron relative to the other electron or the spin measuring device that needs to be accounted for in the spin state of the electrons. This appears to be as close to a “non-relativistic” setup of spin ½ particle correlation as we can get. It is true that an observer of the experiment could be moving with respect to it, but that would only affect the observer’s view of the whole experiment. It would not affect the spin state of one electron differently from the other, as it could if the electrons were flying apart. So we will assume the adequacy of (*) as a description of the joint state for the static electrons in the Hensen et. al. setup.

As we said at the beginning of this discussion, basic quantum mechanics deals with measurement of the spin of the two particles in joint state (*) by implicitly assuming a “non-relativistic” world in which one particle can be measured first. If we want to know what the probability of a measurement leaving the first particle in state v(α, β) is, we cannot just multiply its conjugate transpose by (*). If we measure the first particle before the second, the result will still be a joint state for the two particles. We need to form the tensor product of v(α, β) with something.

Here we can use the fact that (*) and (**) are the same for any choice of

Let’s suppose that the second particle is going to be measured in the direction (γ, δ). We will not need to be specific about what (γ, δ) is, which is just as well. When we make a measurement on the first particle we do not know in what direction the second is being measured in any case. The result of such a measurement on the second particle can only leave that particle in the spin state v(γ, δ) or v(π – γ, δ + π). If the spin state of the first particle is v(α, β) then the joint state of the two particles is either v(α, β) ⮾ v(γ, δ) or it is v(α, β)⮾ v(π – γ, δ + π). Now think of (**) being constructed using (α, β) and (γ, δ) as the directions of measurement. Multiplying the conjugate transpose of v(α, β) ⮾ v(γ, δ) by (**) will extract

the coefficient that that goes with the v(α, β) ⮾ v(γ, δ) term in (**) divided by the normalization constant. Similarly, multiplying the conjugate transpose of v(α, β)⮾ v(π– γ, δ + π) by (**) will produce the coefficient associated with v(α, β)⮾ v(π– γ, δ + π) in (**), again divided by the normalization constant. The probability that one of these two mutually exclusive tensor products states will obtain after measurement on the two particles will be the sum of the squared moduli of their coefficients in (**), divided by 2. One of the squared moduli of these two coefficients will be

and the other will be

where ξ is the great circle distance between (α, β) and (γ, δ). So the probability that v(α, β) ⮾ v(γ, δ) or v(α, β)⮾ v(π– γ, δ + π) obtains is just

Now v(α, β) can only be the result of a measurement on the first particle if one of these two tensor product states obtains for an unknown measurement direction on the second particle. But whatever that unknown direction is, the probability of being in the state v(α,β) after measuring in the (α, β) direction is ½. Similarly, the probability of being in the state v(π– γ, δ + π) after measurement is also ½. Prior to measurement we say that in the direction (α, β) the first particle is in a mixed state with probability ½ of having spin ½ and being in the associated state and probability ½ of having spin –½ and being in its associated state. The probability of either spin as measured on the first particle is unaffected by what direction the second is to be measured in. (Thus the spin correlation of the particles cannot be used for superluminal communication.)

Now, as can be seen by the above discussion, putting the first particle in one of two possible spin states eliminates two of the four tensor products in (**). The two remaining tensor product states have different probabilities, one which will be

and the other of which will be

The factor of ½ disappears once the state of the first particle is determined. The outcome of measurement on the first particle is not known when the second is measured, so the probability of either possible outcome would appear to be ½ for the second particle too. Again, no possibility of superluminal communication. But if the first particle is measured “first”, the probabilities of the two outcomes for the second particle spin are now different. These new probabilities have been determined superluminally. This is the “spooky action at a distance.”

The last two paragraphs may seem to contradict each other, but recall that an observer local to the impending measurement of the spin of the second particle cannot know what the spin of the first particle is. From that observer’s perspective the probability of either spin result for the second particle remains ½.

Things work out in a “non-relativistic” world, allowing for some “spooky action at a distance.” Now let’s add the restriction that under special relativity, neither of two measurement events, which have a spacelike relationship, can be considered “first”. What if we just say that it is not important, let both measurements be “first”. If measurement on the first particle spin leaves it in the state v(α, β), there is some possibility that the second particle will be in the state v(γ, δ) and some that it will be in the state v(π– γ, δ + π) after measurement. But if “first” is not important, and if after measurement, the second particle is in spin state v(γ, δ), it must be possible for the first particle not to be in spin state v(α, β). Yet we just specified that the first particle is in that state after measurement.

We have explained this conflict in terms of quantum mechanics, which we believe, and experiment indicates, applies to correlated spin ½ particle pairs. We can be less restrictive. If the spins of the particles are ½ or –½, the spins have standard deviation 1 and the correlation of the two spins is given by -cos (ξ/2) for great circle angle ξ between the spin measurements, conditions which apply in the case of the quantum mechanical model, then there is no local model which will accommodate this situation. Bell’s inequality or the equivalent will be violated. In other words, the experiment cannot be modeled in such a way that each of the two spin measurements can be treated as “first”.

It seems that the two spin measurements need to be made at the same space-time point, yet the experimental setup appears to forbid this. Well, let’s work on a “simple but alien” out. Suppose we have an electron of unknown spin state, which we treat as a mixture, having probability ½ of having a spin ½ in any direction. When we set up an apparatus to measure the spin of the electron in the direction (α, β) we are typically using some convenient reference for directions, such as a perpendicular to the floor. So α=0 would correspond to the direction straight up from the floor. β=0 could be based on any convenient horizontal reference, such as a cardinal direction.

If the measurement produces a spin of ½, we say the particle is in state v(α, β). But suppose we now decide that α=0 corresponds to straight down direction, and β has become β+ π. The co-ordinate system of the unit sphere has been turned upside down and the electron is now in the v(π-α, β+π) state in the new co-ordinates. The point is we can randomly pick a direction and measure to determine the state, or we can treat the measurement device somewhat like a stick that is labeled ½ at one end and –½ at the other and rotate the world randomly about it. One way seems natural and the other silly, but mathematically they are the same.

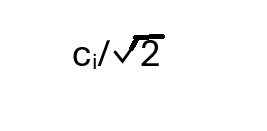

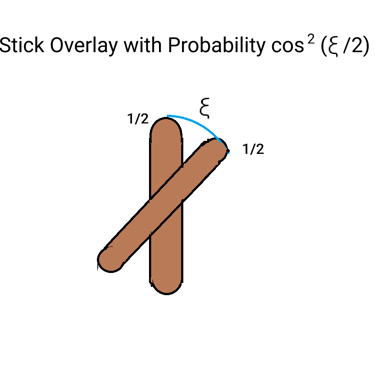

Think of an electron as a tiny stick that is labeled ½ at one end and –½ at the other. Now overlay it with a stick of the same size so that the two sticks intersect at the middle. Let

be the probability that one end of the new stick be labeled ½ when ξ is the angle between the segment of the new stick from that end to the center and the segment of the original stick from the ½ label to the center.

If ξ=0 we are assured that the candidate end of the new stick will have the ½ label. This is just the behavior of the probability that an electron (or any spin ½ particle) will have spin ½ in a new direction given it had spin ½ in a given direction. Only the angle between the directions matters. The quantum mechanical states associated with the two directions are more complicated because they incorporate whatever convenient co-ordinate system we are using to relate to the particle.

The situation with two spin ½ particles in the joint state (*) is very similar. Because the two particles cannot have the same spin in the same direction, the probability that two overlaid “sticks” representing the particles will have the same spin for an angle ξ between the endpoints will be

Again, only ξ really matters. The state (*) again relates the particles to some convenient co-ordinate system. Yet the state (*) is not really dependent on any co-ordinate system. It represents a system with joint spin 0, and there is no preferred direction. Rotate the co-ordinates in any way and you still have (*).

As long the angle ξ is unknown because of the spacelike separation of the particles and measurement of spin has not yet been performed, even having different co-ordinate systems for the two particles does not change the state (*). Suppose the spin to the “Left” is what experimenters local to each particle are to measure, but different co-ordinate systems are being used for each particle. Each of these systems can be translated into a common co-ordinate system, say the one on which the particular representation of (*) is based. In terms of the common co-ordinates, (*) will now look like (**). (If an experiment is set up in such a way that the two particles are local to each other, and spin measurement directions are determined but the spin measurements are yet to be made, then (*) is still preserved. This is obviously not an experimental setup which exhibits “spooky action at a distance”, however.)

Suppose now that measurements are performed on the spin of the two particles, but they still have a spacelike separation. Suppose we ignore what the experimenters think of as their orientation in space and say the co-ordinate system is yet to be determined. In that case we just have what amounts to the stick with label ½ at one end and –½ at the other with no defined orientation. There is no local state collapse. The ½ end is equally likely to occur in one direction as in the opposite direction, so it remains in the mixed state it had under (*). Has the state (*) of the entire system been changed? Well, look again at (**). The four tensor product states that comprise (**) simply represent four ways to bring the two “sticks” together with angle ξ between them, the only difference between the four being the arrangement of the labels ½ or –½ at the ends. All the measurements on each particle are doing is making the “stick” end labels for each particle visible to its local experimenter. Without a fixed co-ordinate system for both particles (*) is preserved.

Continuing in this vein, when does (*) collapse? Say synchronized clocks are available at both ends of the experiment. Suppose the spins of both particles are measured at the same time according to these clocks. An observer located halfway between the two measurement points can receive information about the results of both measurements simultaneously. This observer sees the results for each particle of the spin measurement in a direction relative to some visible reference points. The reference points are matched up, giving the angle ξ between the now labeled “sticks”. Now only one of the four tensor product states in (**) applies. We have collapse. The information about the individual measurements on the two particles reaches the observer at light speed. No superluminal communication between the particles as their spins are measured is required. Information proceeds from the measurements to the observer at the speed of light. No “spooky action at a distance”.

This is the “simple”. Perhaps a little hard to follow, but compared to, say, developing a model in which the particles communicate through wormholes, the above is a snap. (No shade on those who want to work on the “spooky action” problem in the context of general relativity, which we are not. More power to them.) The “alien” is obvious to those who have looked at an issue that has been around since Einstein, Rosen, and Polosky looked at it 90 years ago.

At a concrete level, one could object that, “Heck, I know that my apparatus and the remote one for the other particle are measured with respect to parallel floors and matching cardinal directions. Even before I can know what the measurement on the other particle spin is, the measurements are set, the system has to be collapsed, and I only wait for the already determined results to come in. The other experimenter is not going to measure spin with his floor at some random angle to mine.” Well, actually, if the earthquake only affects one floor, the observer halfway in between might not see parallel floors. A bit silly, but more to the point is that (*) does not require the two particles to share co-ordinate systems with ξ undetermined. The floor and cardinal direction is the experimenters’ bias.

Even at collapse, to give an example, if ξ= π/2, it does not matter whether the spin of one particle was measured straight up and the other parallel to the floor, or if the first was measured at a 10 degree angle to the local floor, but that floor is joined the floor for the second particle at an 80 degree angle. Measurements on the spins of the two particles, in directions based on the floors and cardinal direction associated with each measurement, can be brought together with the floors and cardinal direction aligned to produce a ξ, but there are an arbitrary number of ways to bring measurement directions, floors, and cardinal directions together to produce the same ξ. The fact that an observer will be “fusing space together” in the natural way to produce ξ does not in itself mean that the spin measurement on each particle must be considered to have a specified co-ordinate system before the simultaneous observation of both measurements occurs.

It is perhaps primarily the geometric representation of special relativity that motivates the view that the measuring of the spin of each particle must cause state function collapse before the angle ξ is observed. The representation is four dimensional, with of course one dimension of time and three of space. We represent the space-time points at which the two particles are measured as two points at the base of future light cones that intersect in the futures of both space time points. But we imagine the measurements there, in the representations. We figure we can imagine them in our geometric representation and impute the ξ that will be revealed when their future light cones intersect. This implies collapse to us right at the space-time points of the measurements, even though figuring out how these measurements “communicated” to determine ξ superluminally is problematic.

What is being overlooked here is that, neglecting a week gravitational field, we are living in this four dimensional world we are modeling. The thought process described above leaves us and our perceptive processes out of the model. How do we model ourselves simultaneously perceiving the two space-time points of the spin measurements? Logically, we model ourselves receiving information delivered at light speed from each of these space-time points, which are now in our past. So we model ourselves somewhere in the intersecting future light cones of these points. No different from reality, and not in conflict with our idea that (*) does not collapse until the spin measurements for the two particles is simultaneously received.

After more than a century of quantum mechanics, it is alien to go against the view that a measurement on an initial state, if observed, even only locally, must entail some kind of state collapse. But we have made an argument that, in the special case of two static elections in state (*), collapse does not occur just because we have made a local measurement. The alternative, that some sort of superluminal communication is going on, seems even more alien.

One more issue should be addressed regarding the proposed way that collapse happens to (*). Again, suppose measurements of spin for the two particles are made when synchronized clocks show the same time. We can say collapse occurs when the results are transmitted at light speed to the point halfway in between the measurements. But this is not the only possible collapse point. If that were true, any other point in space time where the results have just been fully received would have to be in the future of that one collapse point. In fact, that cannot be the case. Imagine a plane perpendicular to the line between the measurements, a plane which includes the halfway point. Take a different arbitrary point on that plane. Information about both measurement results will reach this point simultaneously. Now think of the path of light from a measurement to the halfway point and then to the arbitrary point. The path from a measurement to the arbitrary point is one side of a triangle of which the path via the halfway point constitutes the other two sides. In other words, the path including the halfway point must be longer. This means that by the time information about the measurements reaches the halfway point at light speed, it is too late for this information to reach the arbitrary point before it already has received the information directly. So collapse occurs at two space-time events which have spacelike separation. In fact, by the same reasoning, collapse will occur eventually anywhere on the plane in an event that has spacelike separation from every other collapse event at a point on the plane. (A little thought will show that, for any point off the plane, information on one spin measurement of a particle will reach it first. The event “the other spin measurement result reaches the point” will necessarily be in the future of some collapse event on the plane. Points off the plane cannot be the site of collapse events.)

So what is to prevent different results of collapse at different points? Again remember our analogy, viewing the results of the measurements as sticks labeled ½ at one end and –½ at the other. Each has its orientation to its floor and cardinal direction. If we bring information on them together in the natural way, the result is the same regardless of where the information is first received jointly. Note that even for an experiment that involves a measurement in only one place, having two observers on opposite sides of the experiment makes the question of exactly when collapse occurred unclear. But consistent collapse does occur. Yet a “plane of collapse” does make the suggested solution to collapse of (*), though consistent, seem even more alien. (If the measurements of spin for the two particles is not performed at the same time on their respective synchronized clocks, a curved surface replaces the “plane of collapse”. Collapse remains consistent.)

Two static electrons with joint spin (*) is, as we have indicated, a special case endowed both with simplicity and a great deal of symmetry to work with. There are many examples of spin correlated particles, from light rays to top quarks, with different joint distributions from (*). Whether enough symmetry can be found to argue that separate measurements on the particles do not collapse these joint distributions until the measurement information is brought together is an interesting question inviting further investigation.

Comments on the above?

Email:

comments@simbalien.org